Vibratory stress relief

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Vibratory Stress Relief, often

abbreviated VSR, is a non-thermal stress relief method used by

the metal

working industry to enhance the dimensional stability and

mechanical integrity of castings, forgings,

and welded components,

chiefly for two categories of these metal workpieces:

-

-

Precision components, which are machined or

aligned to tight dimensional or geometric tolerances.

Examples include machine tool bases or columns,

components of paper

mill, mining

equipment, or other large-scale processing

machinery, and centrifuge rotors.

- Heavily loaded

metal workpieces, which are components designed and

built with the ability to withstand heavy loads.

Examples include lifting yokes, clamshell buckets, crane

bases, vibratory screening system frames, ingot

processing equipment, and rolling

mill equipment.

These stresses are called residual

stresses,[1] because

they reside within the metal workpiece. Residual stresses are

caused by rapid, unequal cooling as opposed to the stresses

caused by external loading. This unequal cooling occurs during

welding, casting, forging, rough machining or hot

rolling. These stresses often lead to distortion or warping of

the structure during machining, assembly, testing, transport,

field-use or over time. In extreme cases, residual stress can

cause structural

failure.

Almost all vibratory stress relief equipment

manufacturers and procedures use the workpiece’s own resonant

frequency to boost the loading experienced by induced

vibration, so to maximize the degree of stress relief achieved.

Some equipment and procedures are designed to operate near, but

not at, workpiece resonances (perhaps to extend equipment

life)(example WIAP research,[2] but

independent research[3] has

consistently shown resonant frequency vibration to be more

effective. See references 4, 6, and 9.

The effectiveness of vibratory stress relief

is highly questionable.[4] In

general, the strain amplitudes achieved during vibratory stress

relief are too low to exceed the critical stress required to

activate mechanical relaxation during the induced low amplitude

high cycle fatigue excitation of the transducer vibrations. If

the strain amplitudes were increased to a level sufficient to

cause instability in the residual stresses, fatigue damage would

occur.[5][6] For

most applications, conventional stress relief methodologies

should be applied to components that require the reduction of

residual stresses.[7]

Criteria for effective VSR treatment[edit]

Effective vibratory stress relief treatment

results from a combination of factors:

-

1. Material condition: The

material must be ductile.

Metal in the welded, cast, forged, or hot-rolled condition

can be treated. Material that has been severely cold-rolled

or through-hardened, which renders the metal non-ductile,

will resist effective treatment.

-

2. Component geometry: Large workpieces lend

themselves well to vibratory stress relief, likely due to

their being more able to be resonated, however a variety of

modest-sized workpieces (overall size less than 20" / 500

mm) have been effectively stress relieved, using vibration.

-

3. Setup for VSR Treatment involves several steps.

- Placing workpiece

upon load cushions. These cushions should be made of

soft, yet resilient material, typically urethane or

neoprene. The cushions should be placed away from the

corners of the workpiece, so that workpiece damping is

minimized, which promotes increased resonant response to

vibration.

- Positioning,

orienting, and securely clamping vibrator on workpiece. The

vibrator should be placed away from the corners of the

workpiece, and oriented so that the force-field output

of the vibrator, with rotary vibrators a plane

perpendicular to the vibrator’s axis of rotation, can

drive the workpiece into resonance. Dual-mount-flanged

vibrators are helpful in achieving effective

orientation. The vibrator must be securely clamped,

typically with machinist-grade clamps or high-tensile

bolts.

- Positioning and

orienting vibration sensor. The best location for

this sensor is on one of the corners of the workpiece,

and in-line with the force-plane of the vibrator (a

plane perpendicular to the vibrator’s axis of rotation [AOR]).

- Adjustment of the

vibrator unbalance. The unbalance of the vibrator

should be sufficient to drive the resonances of the

workpiece, minimally to a level of a few g’s of

acceleration. The unbalance might require further

increase, to cause peak growth (discussed later) during

stress relief treatment.

-

4. Finding Resonance(s). The vibrator speed range

must reach high enough to be greater than the resonance(s)

of the workpiece. A max speed capability of at least 6000 –

8000-RPM is recommended. Equally important is tight vibrator

motor speed regulation (±0.25%), which greatly improves the

ability to detect and drive the resonance(s) (abilities that

are required for stress relieving to occur). Driving a

resonance involves tuning the vibrator speed to the top of

the resonance peak. This is increasingly challenging as

workpiece rigidity increases, which causes resonances to

become very narrow. To record such resonances, a slow,

automated scan through the speed range and plotting of the

vibration response of the workpiece is made.

-

The scan rate must be slow, not only because the resonance

peaks are narrow, but also due to the high-inertia of the

workpiece. There is a significant time delay, caused by this

high workpiece inertia, in the response to vibration. This

can be best explained by first looking at the phenomenon

known as ring time.

-

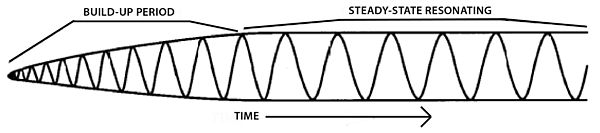

Ring time is defined as the time period a resonating body

continues to vibrate after resonant excitation is stopped.

When the vibration is stopped, the waveform will decay, ie,

reduce in amplitude, due to frictional losses. See Figure

1

-

Figure 1: A waveform that demonstrates

ring time, which is the time period vibration

continues, after resonant excitation ceases.[8]

-

Most people have experienced ring time. A large bell, after

being struck, continues to emit sound, but at decreasing

(softer) sound levels. Over time, the sound level

dissipates, as the vibration amplitude decays to an

undetectable level.

-

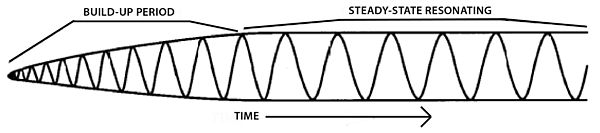

When vibration is the excitation causing resonance (rather

than a hammer blow [such as the strike of a bell]), there is

a time period between the beginning of vibration excitation,

and the moment when full resonant amplitude is reached.

During this time the amplitude is building-up or growing

(the reverse of decaying), so this phenomenon is called

reverse ring time, or RRT. For large metal structures that

are commonly stress relieved with vibration, ring or reverse

ring times (the time periods are the same, whether the

amplitude is growing or decaying), can be 20 – 40 seconds or

longer. See Figure 2.

Figure 2: Reverse ring time, or RRT, is

the time period between the start of vibration

excitation, and full resonant amplitude.[9]

-

The most frequently used method of finding the resonances of

a workpiece during vibratory stress relief is to scan

through the vibrator speed range, and record / plot the

vibration amplitude vs. the vibrator speed. The effect of

RRT, specifically the time delay between the beginning of

resonant vibration and full resonant amplitude being

achieved, dictates that the scan rate used to sweep through

the vibrator speed range be slow, in order to make an

accurate record of the resonance pattern.

-

Scanning too quickly will result in resonant peaks not being

fully depicted or being missed entirely, since the workpiece

will not have sufficient time to reach full amplitude

resonance before the vibrator speed increases (due to

scanning) beyond the resonance frequency.

-

A scan rate of 10-RPM / second has been found in practice to

result in the accurate resonant peaks recording of many

workpieces. As workpiece size increases, the scan rate might

require being decreased, in order to fully capture accurate

resonance data. See Figure 3.

Figure 3: The effects of scanning at

different scan rates: 10 and 50-RPM/sec. Peaks

that are scanned too quickly don't have enough

time to reach full resonant amplitude, due to

the RRT effect. The larger and heavier the

structure, the greater the inertia, the longer

the ring time (and reverse ring time): Thus,

larger, heavier structures might require slower

scan rates to plot accurate resonance patterns.

-

5. Tuning Vibrator Speed. The vibrator speed is then

tuned upon the resonance(s) recorded during the scan, and

the response of the workpiece to vibration is monitored.

Fine tuning of the speed, plus tight speed regulation,

enhances peak tuning and tracking capabilities. The most

common responses to treatment are:

-

Peak Growth - Typically the larger change.

-

Peak Shift, in the direction of lower RPM -

Percentage-wise, the smaller change. Typically resonance

peaks are very narrow, causing any peak shifting to

rapidly decrease the vibration amplitude, and hence,

rapidly decrease of the rate of stress relief, since

resonant amplitude is more effective in relieving

stress. Thus, any peak shifting requires fine-tuning

adjustment of the vibrator speed, in order to track the

peak to its final, stable position.

Each of these changes, which often combine,

i.e., peak growth AND shifting, is consistent with a lowering of

the rigidity of the workpiece. The workpiece rigidity is

inflated by the presence of residual stress. In the example

below, which depicts a common resonance pattern change that

occurs during vibratory stress relief, the large peak grew by

47%, while simultaneously shifting to the left 28-RPM, which is

less than 0.75%. See Figure 4.

The equipment used to perform this stress

relief had vibrator speed regulation of ± 0.02%, and speed

increment fine-tuning of 1-RPM, which allowed even subtle

shifting of the peaks to be accurately tracked to their final,

stable locale.

The pattern of change, i.e., how quickly the

peaks grow and shift, is faster at the beginning of vibration

treatment: As treatment continues, the rate of change decreases,

eventually resulting in a new, stable resonance pattern.

Stability of this new resonance pattern indicates that

dimensional stability of the workpiece has been achieved.

Figure 4: VSR Treatment Chart consists

of two plots: The upper plot is workpiece

acceleration, the lower plot is vibrator input

power, simultaneously plotted vertically vs. a

common horizontal axis of vibrator speed. Peaks

in the acceleration data depict resonances;

growth and shifting of the peaks are the

response of the workpiece to treatment.

The power plot is useful in both positioning

and orienting the vibrator, and when adjusting the vibrator

unbalance. Poor or inappropriate vibrator locations or

orientations, or excessive vibrator unbalance settings, cause

large peaks in the power plot. Use of higher-powered vibrator

motors (above 2-kW) provides more "head-room" for peaks in power

to be tolerated, and treatment to take place, which was the case

here: The power peak at ≈ 3700-RPM was only half of the vibrator

motor’s 2.3-kW power capacity (top of the power scale).

A Pre-Treatment Scan, which functions

as a base-line, is first recorded in green. The operator uses

this green data set to tune upon the resonances, and monitor the

growth and shifting of the resonance peaks. After peak growth

and shifting have subsided, a Post-Treatment Scan is made

(red). This data is superimposed on the original, green,

Pre-Treatment Scan data, documenting the changes in resonance

pattern. The stress relief treatment resulted in 47% growth of

the original, large peak, while it shifted to the left 28-RPM

(less than 0.75%).

Figure 5: Vibratory Stress Relief was

performed on this mild steel weldment weighing

almost 12 tons. Overall size was 17' × 15' × 2'

(≈ 5.2 × 5.6 × 0.6 meters). Workpiece was

supported on three, red urethane load cushions

(two of which are circled), which are positioned

far from the corners of the workpiece to

minimize damping, thus promoting resonance,

which is required for stress relief to be

achieved. The vibrator can be seen in the left,

mid-ground (circled), and the accelerometer

(vibration sensor whose output is proportional

to acceleration), can be seen in the central,

left, foreground (circled).

After stress relief treatment, the braces

(rust-colored, structural beams), which are used to maintain the

desired shape during welding, were removed. The spacing between

the two "arms" remained the same; no change was detectable

(measured to 1/32" or less than 1 mm), and the spacing remained

so throughout assembly, testing (to 60 ton test loads),

transport, and installation.

When should VSR be considered and the limits of TSR[edit]

VSR is not accepted by the Engineering

community at large as a viable method of relaxing or reducing

residual stresses in components that require it. For general

use, conventional residual stress relaxation methodologies are

recommended.[10]

Historically, the first type of stress relief

was performed on castings by storing them outside for months or

even years. This was referred to as curing, a term used

for long-term storage of freshly hewn wood. Fresh castings were

referred to as being green, meaning, they were prone to

distortion during precision machining, just as green wood

bows during cutting.

Later, thermal stress relief (TSR) was

developed to alleviate the lengthy time requirements of curing.

It has been known for many years, however, that TSR has

limitations or shortcomings, specifically:

-

-

Furnace size: workpieces can be too large to fit.

- Not effective on all

alloys, among them austenitic stainless steels.

- Should not be used on

welded structures made of low-carbon, high-strength

steels, which can suffer loss of physical properties

and/or crack initiation if thermally stress relieved.[11][12]

- Cannot be used on

workpieces that have been quenched and tempered (Q&T)

without risking loss of physical properties. Vibratory

stress relief can be successfully applied, if some level

of ductility is present after Q&T, together with

acceptable workpiece geometry (which determines resonant

vibration frequency required).

- Often not suitable for

rough-machined components, due to difficulty in removing

scale (rust-colored skin that develops on ferrous

components while in-furnace), without damaging machined

surfaces.

- Asymmetrical-shaped

workpieces, which are difficult to cool while

maintaining uniform temperature, can develop new,

unacceptably high-level, residual stress patterns during

the last stage of TSR. Cooling rates can be slowed, but

with increased costs.

Metal components, whose function would be

enhanced by stress relief, and fall into one or more of the

above categories, are strong candidates for VSR for

quality-related reasons.

Further, there is a strong economic incentive

to use vibratory stress relief on large workpieces, since stress

relief using a furnace (thermal stress relief or TSR) is highly

energy-intensive; consuming much natural gas, and hence,

producing much CO2.

The cost of TSR is approximately proportional to a metal

component’s weight or overall size, estimated to be $2,500 USD

for the structure pictured, plus transportation costs, which

might involve special transport permits, to and from a furnace.

VSR Treatment would cost a company owning appropriate equipment

less than 15% as much ( ≈ $400 ) as TSR Treatment, chiefly

amortization of equipment investment plus labor, and a modest

amount of electrical consumption, and treatment would take less

than two hours, with no transport required. However, the lack of

independent data to show that this technique is effective may

mean that even that lesser investment is not of any value, so

use of VSR should evaluated very carefully before proceeding.

References[edit]

-

Notes

-

Jump up^ [1] R.T.

McGoldrick and H. Saunders, Some Experiments in

Stress-Relieving Castings and Structures by

Vibration, Journal of the American Society of Naval

Engineer., 55, 589-609 (1943)

-

Jump up^ [2] Wiap

Stress relief since 1981

-

Jump up^ [3] R.

Dawson and D.G. Moffat, Vibratory Stress Relief:

A Fundamental Study of Effectiveness, Journal of

Engineering Material and Technology, 102,

169-176 (1980)

-

Jump up^ J.

Stubbs, "Vibratory/Thermal Stress Relief in a Weld

Joint", Case Western Reserve University, 2003.

-

Jump up^ G.

Totten et al. "ASM Handbook of Residual Stress and

Deformation in Steel", 2001 p.54-67

-

Jump up^ [4] R.

Dawson and D.G. Moffat, Vibratory Stress Relief:

A Fundamental Study of Effectiveness, Journal of

Engineering Material and Technology, 102,

169-176 (1980)

-

Jump up^ ASM

Metals Handbook, Volume 4, "Heat Treating, Cleaning

and Finishing", 1991

-

Jump up^ [5] C.A.

Walker, A.J. Waddell and D.J. Johnston, Vibratory

Stress Relief - An Investigation of the Underlying

Process, Proc. Inst. Mechanical Engineers., 209,

51-58 (1995)

-

Jump up^ [6] S.

Shakar, Vibratory Stress Relief of Mild Steel

Weldments, PhD Dissertation, Oregon Graduate

Center, U. of Oregon, 1982

-

Jump up^ ASM

Metals Handbook, Volume 4, "Heat Treating, Cleaning

and Finishing", 1991

-

Jump up^ [7] B.B.

Klauba and C.M. Adams, A Progress Report on the

Use and Understanding of Vibratory Stress Relief,

Proc. Winter Meeting of the ASME AMD 52, 47-57

(1982)

-

Jump up^ [8] W.

Hahn, Report on Vibratory Stress and

Modifications in Materials to Conserve Resources and

Prevent Pollution, Alfred University (NY),

Center for Environmental and Energy Research (CEER),

2002

-

Bibliography

PDF D. Rao, J. Ge, and L. Chen, Vibratory Stress Relief

in the Manufacturing the Rails of a Maglev System, J. of

Manufacturing Science and Engineering, 126, Issue 2, 388-391

(2004)

PDF B.B. Klauba, C.M. Adams, J.T. Berry, Vibratory Stress

Relief: Methods Used to Monitor and Document Effective

Treatment, A Survey of Users, and Directions for Further

Research, Proc. of ASM, 7th International Conference: Trends in

Welding Research 601-606 (2005)

PDF Y. Yang, G. Jung, and R. Yancey, Finite Element

Modeling of Vibratory Stress Relief after Welding, Proc of ASM,

7th International Conference; Trends in Welding Research547-552

(2005)

|

|